Let’s face it.

The 8-hour journey from Phonsavan to Luang Prabang was horrible.

It was unforgettable for all the wrong reasons.

My friend was stopping the car every few kilometres or so to puke her guts out, while in the back seat, another of my friend was lying still, trying to hold in the contents of his lunch.

The car tossed and turned as it navigated the twisty mountain roads.

I started getting uncomfortable as well.

The minutes crawled by.

I wondered if the journey would ever end.

Perhaps we were too ambitious.

The day before, we had just arrived in Phonsavan in Xieng Khouang Province after an exhausting 15-hour journey from Vinh in Vietnam.

The bus was packed to the rafters, and after numerous stops to pick up passengers and goods, and a one hour breakdown in the middle of nowhere and in complete darkness in Laos, you can imagine the relief we felt when the bus finally rolled in to Phonsavan.

After waving goodbye to our erstwhile companions as the bus continued on its journey to Luang Prabang, we quickly put our stuff down at the guesthouse and rested our weary bodies.

We had another long day ahead of us.

Phonsavan was not on our itinerary when we first planned the trip.

We had intended to take the two-day slow boat along the Mekong River from Huay Xai, along the Thai-Lao border, to Luang Prabang.

But that didn’t work out due to various reasons, so we entered Laos via a much less beaten path from Vietnam.

In fact, we couldn’t find much information about this route and the lady who sold us the bus tickets told us the journey from Vinh to Phonsavan would only take six hours!

So much for that!

But while Phonsavan is somewhat a pain to get to, it does attract a small though increasing number of tourists.

Most of them are just there for one reason – the enigmatic Plain of Jars.

And of course, we couldn’t give it a miss either.

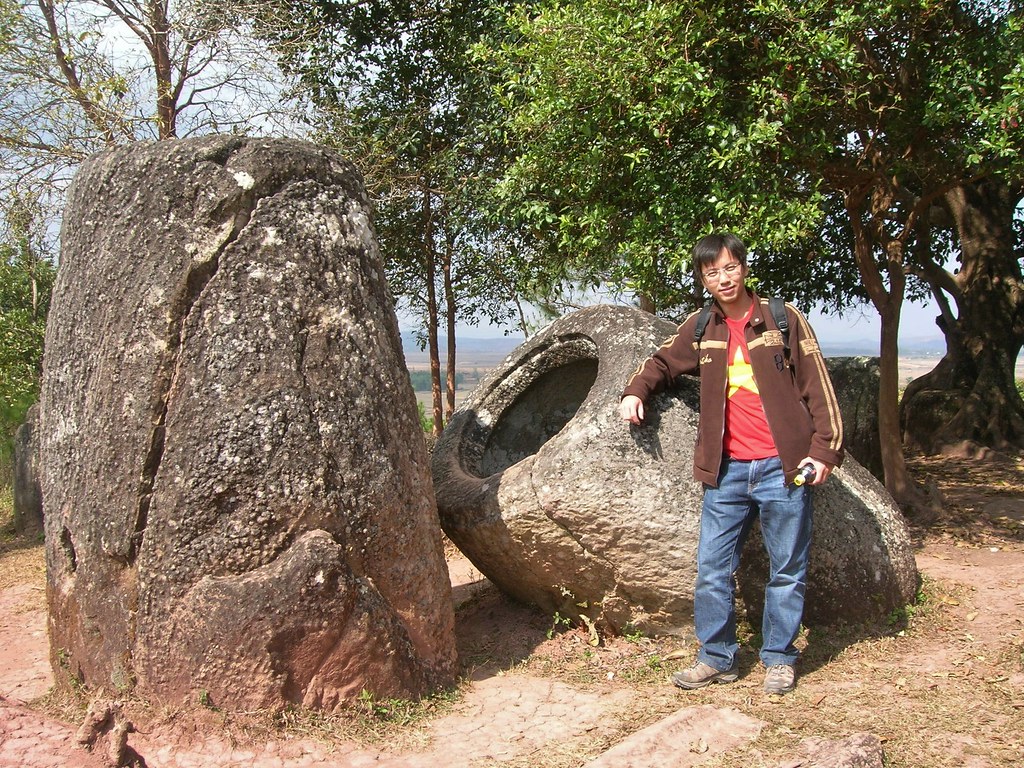

Stone jars, measuring in height of between one and three metres, are scattered throughout the province of Xieng Khouang.

While they’re dated to the Iron Age, no one knows what these jars are used for, and why they were constructed.

Some experts have suggested that they were used for prehistoric burial practices, while others say the jars were used to collect rainwater.

Not knowing for sure what the jars were used for, however, didn’t take away anything from our experience.

If anything, it made it more interesting.

The sight of hundreds of huge stone jars littered across the plains of Xieng Khouang makes for an intriguing sight.

And in any case, there’s an element of edge to our sojourn there too.

Xieng Khouang has the dubious distinction of being one of the most heavily bombed provinces in the most heavily bombed country on earth, and thousands of unexploded ordnance (UXO) remain in the ground throughout the province.

These bombs were dumped by the US military during the Secret War of the 1960s and 70s, and continue to disrupt the lives and livelihoods of residents in Xieng Khouang Province.

At the main jars sites, safe routes which have been cleared of UXOs have been marked out for tourists.

But away from these sites, that’s where the deadly wartime legacies continue to lie in wait for their next victim.

There is a UXO-Visitor Information Centre in the center of Phonsavan and we had to go there to find out more about the UXOs.

The statistics were sobering.

Approximately 80 million unexploded UXOs remained in Laos after the war, and more than 20,000 people have been killed or injured as a result of UXO accidents in the post-war period.

But while Laos is still haunted by its past, there are more dimensions to it than just mystery and tragedy.

And for that, we had to head to Luang Prabang.

Some writers may wax lyrical about how Luang Prabang is the land that time forgot.

Well, that’s stretching it a little too far.

New boutique and luxury hotels are sprouting out everywhere, and Luang Prabang being Laos’ premier tourist attraction, is definitely not untouched by tourism.

But is it still charming?

Yes. Utterly.

Every morning, just before dawn, drum beats echo through the city and rows of saffron-cloaked monks appear out of the darkness like apparitions, continuing their age-old practice of making alms rounds across the city.

And along the banks of the Mekong River, while the early morning mist still hovers in the air, the scene is magnetising.

The buildings, too, hark back to a bygone era.

With Laos being a former French colony, Luang Prabang has its fair share of colonial architecture.

While some of these buildings have been spruced up, others remain in varying stages of decay, lending a rather morbid charm to the city.

The skyline is also punctuated by the numerous golden-roofed wats (temples) – so many in fact that the term “what wat” is often heard around town.

Luang Prabang, however, isn’t a large city.

If we had chosen to, we could have seen all its major sights in one day, albeit a long one.

But that would have been regrettable.

We spent days just wandering around the city, walking down the same streets and yet, we were never bored.

That’s really a testament to how skilled at the art of seduction that Luang Prabang really is.

Other cities may paint themselves in garish colours or adorn themselves with bright lights to attract travellers.

But Luang Prabang doesn’t need to.

It slips under your skin with its easy charm without you knowing it, and before long, you’ll be swaying along to its rhythm – one that’s dictated by the rising and setting of the sun.

If you’re not careful, a planned stay of a few days can quickly become weeks and then months and even years.

We got out while we can.

![[PROMO] Vibe Hotel Singapore Orchard celebrates Australia Day offering special rates with free-flow barbeque, drinks, and family fun! [PROMO] Vibe Hotel Singapore Orchard celebrates Australia Day offering special rates with free-flow barbeque, drinks, and family fun! - Alvinology](https://media.alvinology.com/uploads/2023/01/Vibe-Hotel-Singapore-Orchard-Dining-at-ROOS-1024x683.jpg)