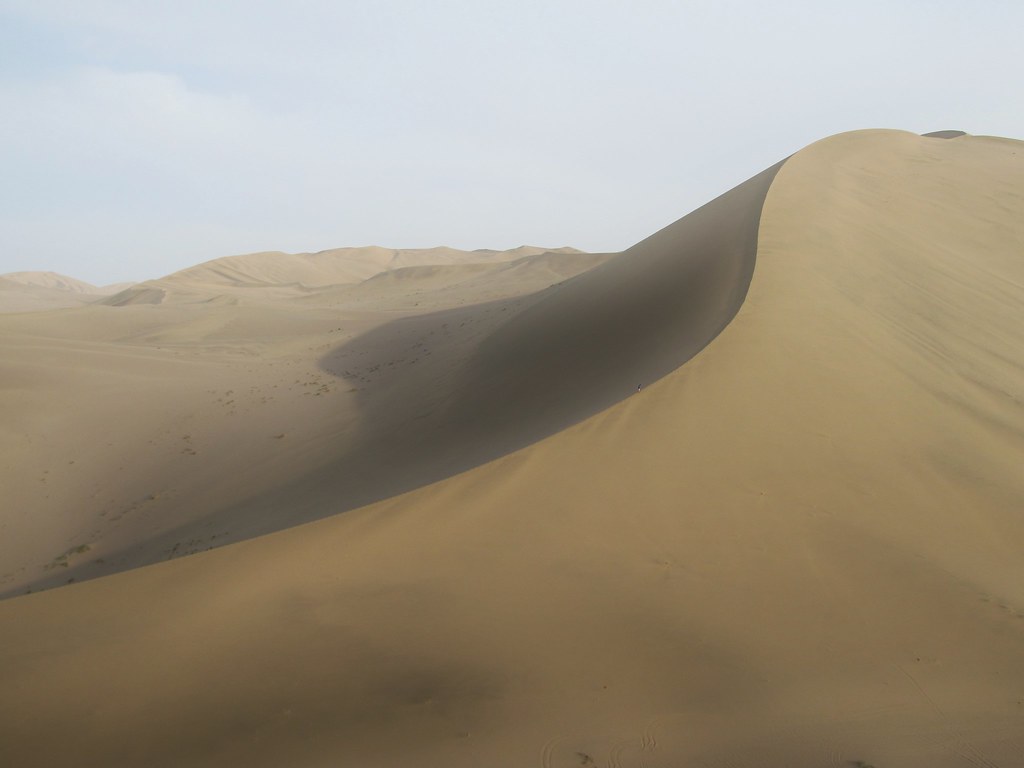

Beads of perspiration dripped from my face as the harsh desert sun beat down relentlessly.

Looking back to see how far I have come, I decided to push on.

But the going was tough.

For every step I took upwards, I slid back half a step.

Finally giving in to exhaustion, I plonked myself down on the sand dune and gave a weary grin to a group of travellers who were attempting the same feat.

We were on the outskirts of the ancient Silk Road city of Dunhuang in western China.

In fact, just six kilometres away.

And amazingly, the road from the city had ended almost at the foot of the pale golden sand dunes that are almost 30 storeys high.

These sand dunes are known as the Echoing or Singing Sand Mountain (Mingsha Shan) due to the sound of the wind whipping off the dunes.

However, the air was still as I attempted to reach the top of one of the dunes, and the only sounds I could hear were of people laughing or encouraging each other as they continued their climb.

Rested, though still not looking forward to the climb ahead, I pushed on.

Eventually, I reached the top.

And despite my fatigue, what a sight it was.

At the foot of the sand dune I climbed was Yueyaquan, a crescent-shaped emerald lake with a Chinese-styled pavilion sitting on one bank, and closed in on all sides by towering sand dunes.

I have seen this sight in numerous pictures (which was what prompted me to travel close to 2,000 kilometres from Tianjin where I lived to this remote city), but as I glimpsed at the shimmering waters of the small lake, it felt like I was witnessing a miracle of the desert.

The famous pool of water has existed for at least two thousand years and has never dried up or been covered by the surrounding sands, though there was indeed that fear a few years back when the water started shrinking into the desert sand due to the falling underground water table.

But fortunately, prompt government intervention has reversed the situation.

Spectacular as the sand dunes and lake were, however, Dunhuang has another jewel up its sleeves – Mogao Caves.

The caves are a legacy of Dunhuang’s emergence more than 2,000 years ago during the Han Dynasty as a crucial entranceway from the West into China by the Silk Road.

And today, they contain one of the greatest repositories of Buddhist art in the world.

Carved out between the fourth and 14th centuries, the grottoes are considerably well-preserved.

Of the almost 800 caves, 492 are decorated with exquisite murals, and some cave interiors are also adorned with sculptures, many of them among the finest of their era.

However, it is not possible to visit most of the caves as entrance to the caves is strictly controlled.

All visitors will be led around on a two-hour group tour of about ten caves, which covers the highlights, but leaves the visitor wanting more.

And much as I wanted to take pictures of the impressive art, I wasn’t able to as photography is strictly forbidden within the site.

Suitably impressed with what Dunhuang had to offer, I decided to head to Jiayuguan, a city along the Silk Road that’s also known as the “mouth of China” because of its position at the end of the Great Wall of China where it guarded the western boundary of Ming Dynasty China.

The narrow river passage heading southeast from Jiayuguan is known as the Hexi Corridor and is nicknamed the ‘throat of China’

At the train station, I was pleasantly surprised to see a group of undergraduates from Xi’an whom I had got to know the day before.

They would become my companions for the four-and-a-half hour train journey to Jiayuguan.

As the train sped across the harsh, rugged desert terrain towards Jiayuguan, my three companions and I shared food, laughed and swapped travel tales, as countless travellers before us have done on that same journey along the Silk Road.

The only difference was, we were travelling in comfort despite the fact that we were travelling on second-class hard seats – the worst in China’s four classes of train travel.

It wasn’t long before we saw the smokestacks and utilitarian buildings on the outskirts of Jiayuguan.

Upon getting off the train, I was struck by how uninspiring the modern town of Jiayuguan was.

There was nothing that recalled the splendour of the fabled Silk Road.

But perhaps my expectations were too high after Dunhuang.

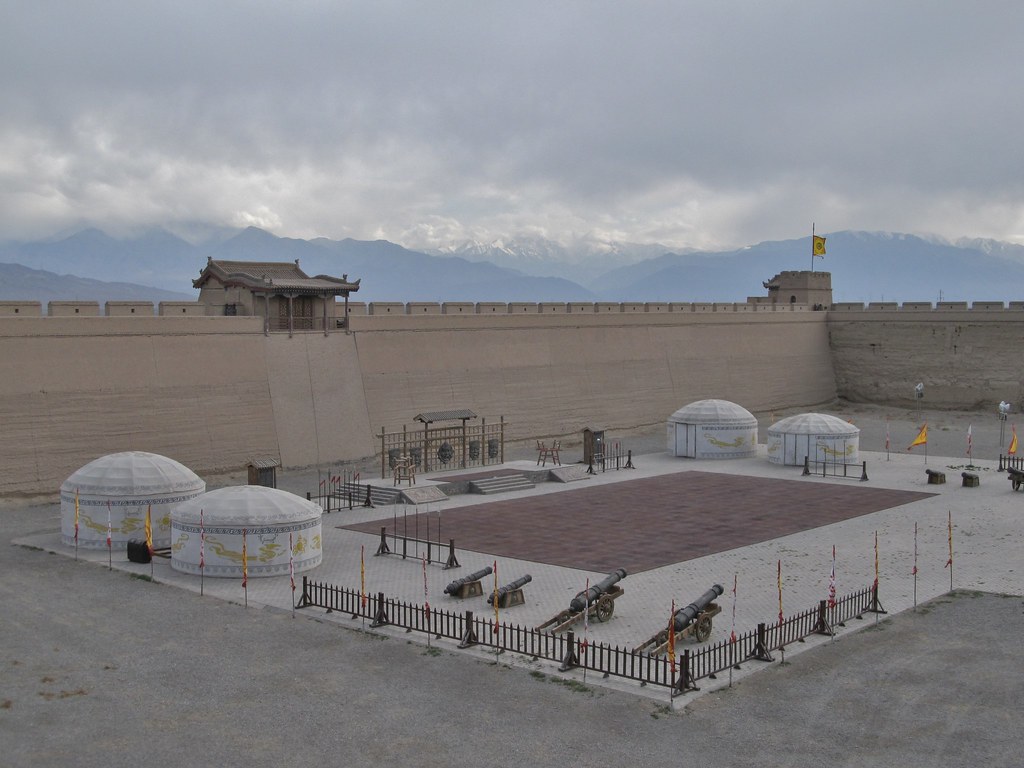

However, my disappointment was soon replaced by awe when I finally set sight on the Jiayuguan Fort – the magnificent mud fortress that was the last outpost of China’s ancient empire, beyond which lay ‘barbarian country’.

Traitors were sometimes banished through its gates and out into the vast desert, never to be heard from again.

Today, the Jiayuguan Fort is the largest and most intact fort of the Great Wall of China.

Standing on it, it’s not hard to appreciate the grandeur of the fort which overlooks the desert and snow-capped mountains to the south.

Given that the fort was the scene of innumerable farewells throughout its history, it was perhaps also fitting that I bade farewell to my companions here as they had to rush off to catch a train.

Back in the city, I started regretting that I did not plan a same-day departure from Jiayuguan as the city had nothing much going for it.

But fortunately, I did not as I would have missed the excellent Wei Jin Tombs if I did.

The tombs were built between the 3rd Century and 5th Century, and the sole underground chamber that’s opened to the public contains extraordinarily fresh, though small paintings offering a rare glimpse into daily life at that time: cooks preparing dinner, musicians playing guitars and so on.

I decided to push on further into the “throat of China” to visit Zhangye, a once famous commercial town on the Silk Road that has lost much of its glory.

Zhangye today resembles any other third-tier Chinese city with its identikit pedestrian malls and fast food joints, so I did not linger long.

Instead, I headed straight for Mati Si (Horse’s Hoof Temple), a temple built into the side of a cliff that’s about an hour’s drive away.

The clouds hung low and a slight drizzle greeted me when I arrived at the little-visited Mati Si, which has long been a pilgrimage site along the Silk Road.

Legend has it that this was where a horse from heaven once left its hoof print, and today, the faint imprint of the legendary hoof print can be seen within the temple complex.

But what’s more intriguing, to me at least, is the complex of Buddhist caves carved into the cliff face that are connected by a series of back-breaking passageways, tunnels, balconies and stairways.

As I re-emerged from the temple complex, the clouds had lifted slightly offering me a magnificent view of the nearby snow-capped mountains.

Shortly after I had snapped a picture, however, they disappeared from view again, as if not wanting to share too many of its secrets.

But that perhaps is what the Silk Road is all about now – much of it hidden under the guise of modern day development.

Still, its treasures await those who look, and from the little I saw, what treasures they are!

![[Review] Be Our Guest to a Night of Enchantment with Disney’s Beauty and the Beast in Singapore This December [Review] Be Our Guest to a Night of Enchantment with Disney’s Beauty and the Beast in Singapore This December - Alvinology](https://media.alvinology.com/uploads/2025/12/Screenshot-2025-12-14-195843-110x110.png)

![[Review] Tim Ho Wan’s Limited Edition East-Meets-West Menu Brings Festive Flavours to Dim Sum [Review] Tim Ho Wan’s Limited Edition East-Meets-West Menu Brings Festive Flavours to Dim Sum - Alvinology](https://media.alvinology.com/uploads/2025/12/6194907278834600928-110x110.jpg)

![[Movie Review] Alien: Romulus (2024): A Terrifying Return to Form, Blending Classic Horror with Sci-fi [Movie Review] Alien: Romulus (2024): A Terrifying Return to Form, Blending Classic Horror with Sci-fi - Alvinology](https://media.alvinology.com/uploads/2024/08/p0jjdrhx.jpg.webp)