This article was first published on August 26 on the International Newsmedia Association’s website.

Though the Great Firewall prevents those in China from accessing sites like Twitter, Facebook, and even Google, there is a rich online culture that makes up an Internet presence most English-speakers don’t even know about.

I have been based in Nanjing, China, for the past two months, working on the global English content for the official Web site of the Nanjing 2014 Summer Youth Olympic Games.

This is also my induction to the Great Internet Firewall of China. Previously, when I traveled to China for work or leisure, the trips were usually no more than a week or so. No Facebook? No Twitter? Fine. It is just a few days. I can live with it.

For two months, this is a problem. You see, Google, Facebook, and Twitter have become so integrated into my daily life — especially Google and its suite of online services ranging from Google Docs to Google Maps to Google Translate and the powerful search engine. They are part of my work tools, improving efficiency and productivity.

For the first few days, I really missed my unregulated Internet. Yes, there are virtual private network (VPN) subscriptions, which can help get around the problem. However, it adds another layer of login and access, which can be quite cumbersome when the Internet network is choppy at times.

After a few weeks, I began to discover the local alternatives. It is adapt or die — Darwin’s theory of evolution. Welcome to the other Internet, the other social media.

According to a report in the Telegraph, there were 565 million English Internet users, compared to 510 million Chinese users, in May 2011. This represents 27% and 24% of total global Internet users, respectively.

It is predicted that if current growth rates continue, Chinese will overtake English as the main language used by Internet users in 2015. This switch is largely due to China’s massive population, now more than 1.3 billion people.

A good quarter of the world’s Internet population is not surfing the Web in English, nor are they using Facebook, Twitter, or even Google. There is another World Wide Web out there.

In the past months, I downloaded WeChat and QQ to communicate with my friends and colleagues in China. Next, I found myself shopping on Taobao, doing online searches with Baidu, and watching videos on Youku.

Yes, the ALS ice bucket challenge is in China too — but it is taking place on Chinese social media platforms.

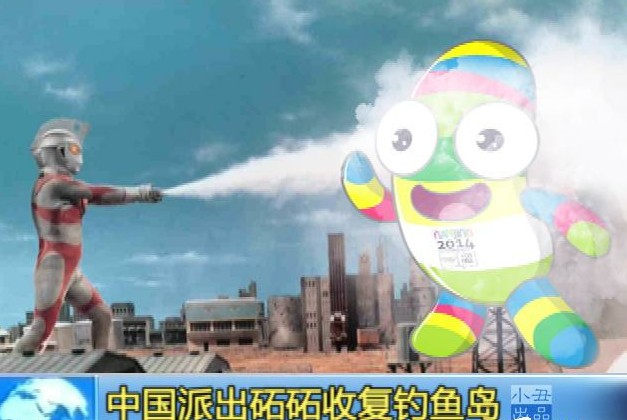

The mascot for the Nanjing 2014 Youth Olympic Games, Nanjinglele, is trending across the Chinese Internet with thousands of spoofs, shares, and reshares. You may not have heard of Nanjinglele outside of China, but he is a crowd-pleaser here.

“In the first 24 hours of the Games the hashtag #YOGselfie was re-shared by 35 million on Weibo and reached an estimated 400-450 million people in China,” said International Olympic Committee Communications Director Mark Adams, during a press conference on the halfway mark of the Nanjing Youth Olympic Games.

Almost half a billion reached in the first 24 hours alone. How many promotional campaigns can achieve that? Admittedly, most of the buzz has been confined within China.

Because of the great Internet and social media divide between China and the rest of the world, trends like the ALS bucket challenge flows into China, but trends in China like Nanjinglele seldom flow out to the rest of the world or create a huge impact globally.

Now I have another set of Chinese apps on my mobile phone and Chinese social media accounts to add on to my existing behemoth list of English social media accounts and apps. I am doing my part to help bridge the Internet and social media in two worlds — one post at a time, across two worlds.