The sudden downpour caught us by surprise.

Scrambling through the neon-soaked streets of Hiroshima to seek shelter, it was when we saw it for the first time.

Bathed in an ethereal green glow, with its skeletal structure standing out against the dark, rainy backdrop.

It was at once eerie and otherworldly.

I thought to myself that it was a perfect first glimpse of the building that was a stark reminder of Man’s capacity for destruction.

It was the A-bomb dome – the most recognisable symbol of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima.

The city of Hiroshima has the dubious distinction of being one of only two cities in the world that have ever had to face the terror of the atomic bomb, the other city being Nagasaki.

It’s estimated that at least 70,000 people were killed after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945.

And the city, which was mostly built of wood, became a charred plain with only a few scattered concrete structures left.

But Hiroshima today has risen from the ashes.

With its blinking neon lights, modern shopping arcades and high rise buildings, it is perhaps no different from any other Japanese city.

Beyond the Peace Memorial Park which surrounds the A-bomb dome, there are only fleeting reminders of the city’s tragic past.

A little plaque here explaining the significance of a place, and a little charred stone there.

After our first glimpse of the A-bomb dome on a moonless, rainy night, we returned to the site again the next morning to find the building bathed in bright sunlight, with clear blue skies, and hordes of tourists taking turns to pose with the infamous building.

What a difference a day makes.

While the building had looked ethereal the day before, it now looked forlorn, as a building bereft of its exterior walls should.

The fact that the building still exists is almost a miracle of fate, as if it wanted to remind the world of what it’s been through.

Because the explosion on that fateful day in 1945 had taken place almost directly above the building, the walls remained largely intact, even as the dome shattered and the people inside were killed by the heat of the blast.

Looking at the building today, it’s hard to believe that more than half a century had already gone by, as it appears frozen in time at that moment of pure unbridled terror.

A stone’s throw away from the A-bomb dome is the simple, yet touching Children’s Peace Monument, which is a statue of a girl with outstretched arms and a folded paper crane rising above her.

The statue is based on the true story of a young girl who died from radiation from the bomb.

She believed that if she folded 1,000 paper cranes, she would be cured.

Today, the monument is perennially draped in thousands of paper cranes folded by schoolchildren across Japan.

In fact, this desire for peace and for a world free from the threat of nuclear annihilation was repeated in the many monuments throughout the Peace Memorial Park.

However, there was a place we had to visit to learn more about the events of 1945 – the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

The museum is split into two wings – East and West.

The East Wing is more educational.

Among other things, it explains the decision to drop the bomb and it also describes the lives of Hiroshima citizens during World War II and after the bombing.

But it’s the West Wing that really pushes home the point about the need for a nuclear-free world.

Besides showing clothing, watches and other personal effects worn by victims of the bomb, it also goes into details about the health effects suffered by the victims.

For some reason, there’s one story in particular which I remember vividly.

It’s about a pair of siblings – a boy and a girl.

The boy had appeared well in the aftermath of the bombing while the sister was suffering from radiation sickness.

However, just a few days later, the boy’s condition took a sudden turn for the worst.

In short, his insides had turned to mush and there was nothing doctors could do to help him.

He passed away shortly, while his sister gradually recovered and became the only survivor of the family.

However, Hiroshima’s not just about the A-bomb and its effects.

There are other attractions, such as the Hiroshima Castle, which is a modern-day reconstruction of the original castle built in the 1590s.

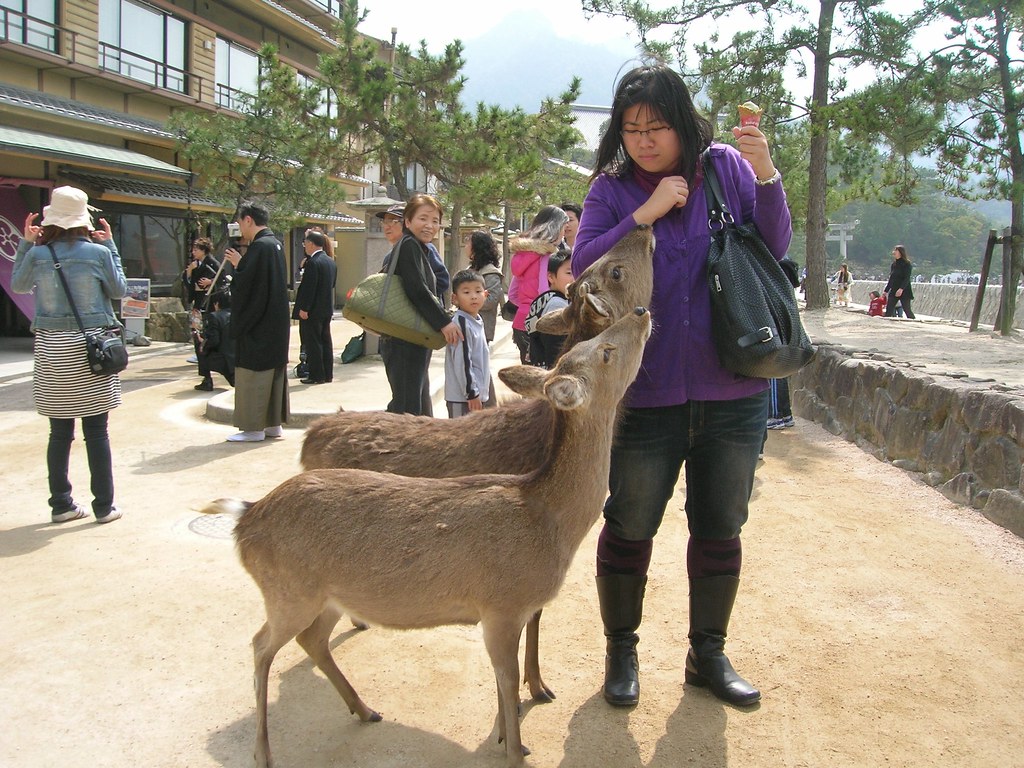

But the truly must-see sight lies just off the coast of Hiroshima, at Miyajima.

Miyajima, which is reached by ferry from Hiroshima, has been considered a holy place for most of Japanese history.

In the past, women were not allowed on the island and old people were shipped elsewhere to die, so that the ritual purity of the site would not be spoiled.

The island is most famous for its floating torii (gate), which appears to float on the sea during high tide.

There’s also the Itsukushima Shrine, a large, red-lacquered complex of halls and pathways on stilts.

Surprisingly, despite the fact that the island is overrun by tourists, it still feels very serene, and is a good respite from modern, bustling Hiroshima.

But back to Hiroshima we had to go, to board a ferry to our next destination.

As the city lights drew closer, a thought struck me – I’ve been to many cities that have fallen into decline for various reasons.

There are also those that have gotten prosperous in the past few decades.

But few have witnessed such scenes of utter destruction, and yet manage to bounce back like Hiroshima has.

And for that, I think the city is not just a symbol for resilience, but also for hope.

Hope that even in the darkest moments, there can be salvation.

![[Review] Fireplace by Bedrock Launches Unlimited Wood Fired Brunch with Festive Treats at One Holland Village [Review] Fireplace by Bedrock Launches Unlimited Wood Fired Brunch with Festive Treats at One Holland Village - Alvinology](https://media.alvinology.com/uploads/2025/12/firestar-by-bedrock-brunch-grilled-25-110x110.jpg)