Singapore is a fast becoming a nation of widening wealth disparity. In the 2013 World Bank report, Singapore has the highest income inequality compared to the economically-developed OECD countries.

Such trends disturb me.

There seem to be two Singapore we live in – one where the mega-rich can live it up and enjoy life to the fullest at our two world-class integrated resorts and the exclusive yacht front residential at Sentosa Cove; the other where old folks scrap by for a living, collecting old cardboards and newspapers in HDB estates, living in rented one room flats.

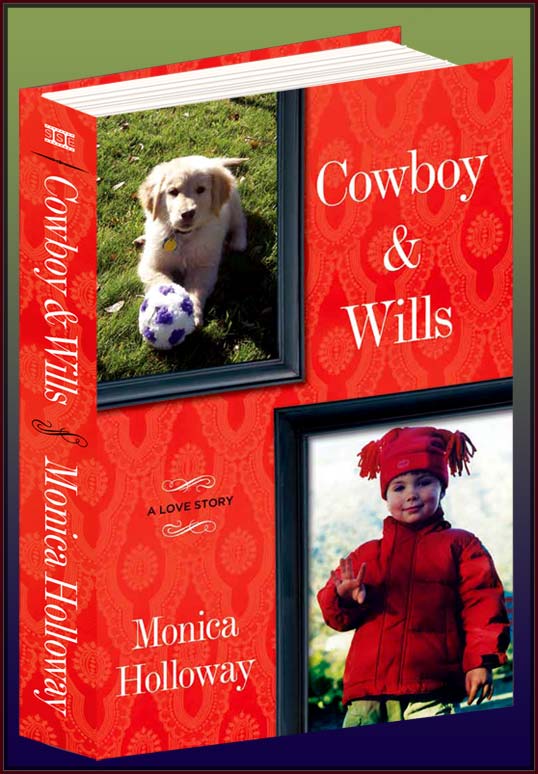

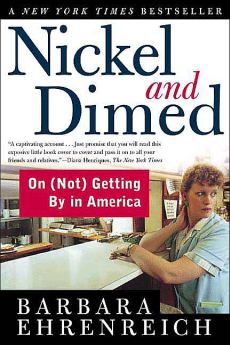

Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America was written from the author’s perspective as an undercover journalist, taking on the role of a minimum wage worker in capitalist United States. The events related in the book took place between 1998 and 2000, but I believe are still very much relevant in today’s context of even widening income gaps due to globalisation.

Here is a summary of the book via Wikipedia:

Ehrenreich investigates many of the difficulties low wage workers face, including the hidden costs involved in such necessities as shelter (the poor often have to spend much more on daily hotel costs than they would pay to rent an apartment if they could afford the security deposit and first-and-last month fees) and food (e.g., the poor have to buy food that is both more expensive and less healthy than they would if they had access to refrigeration and appliances needed to cook).

Foremost, she attacks the notion that low-wage jobs require unskilled labor. The author, a journalist with a Ph.D. in cell biology, found manual labor taxing, uninteresting and degrading. She says that the work required incredible feats of stamina, focus, memory, quick thinking, and fast learning. Constant and repeated movement creates a risk of repetitive stress injury; pain must often be worked through to hold a job in a market with constant turnover; and the days are filled with degrading and uninteresting tasks (e.g. toilet-cleaning and mopping). She also details several individuals in management roles who served mainly to interfere with worker productivity, to force employees to undertake pointless tasks, and to make the entire low-wage work experience even more miserable.

She decries personality tests, questionnaires designed to weed out incompatible potential employees, and urine drug tests, increasingly common in the low wage market, arguing that they deter potential applicants and violate liberties while having little tangible positive effect on work performance.

She argues that help needed signs do not necessarily indicate a job opening; more often their purpose is to sustain a pool of applicants in fields that have notorious rapid turnover of employees. She also posits that one low-wage job is often not enough to support one person (let alone a family); with inflating housing prices and stagnant wages, this practice increasingly becomes difficult to maintain. Many of the workers encountered in the book survive by living with relatives or other persons in the same position, or even in their vehicles.

She concludes with the argument that all low-wage workers, recipients of government or charitable services like welfare, food, and health care, are not simply living off the generosity of others. Instead, she suggests, we live off their generosity:

When someone works for less pay than she can live on … she has made a great sacrifice for you …. The “working poor” … are in fact the major philanthropists of our society. They neglect their own children so that the children of others will be cared for; they live in substandard housing so that other homes will be shiny and perfect; they endure privation so that inflation will be low and stock prices high. To be a member of the working poor is to be an anonymous donor, a nameless benefactor, to everyone. (p. 221)

The author concludes that someday, low-wage workers will rise up and demand to be treated fairly, and when that day comes everyone will be better off.

And we wonder how what triggered the Occupy Wall Street movement?

When I was reading this book, I think back about my experience doing part-time hourly wage job as a teen and all the dirty, manual grunt work I had to do as a NSF. These works were no less tedious than what I am doing now, granted that they were works with low barrier to entry, compared to my current job where specialised knowledge is needed.

Simply put, I believe a road sweeper works just as hard and contribute as much, if not more to society than a Wall Street banker, but the income disparity between the two is staggering and growing wider each day.

I find it uncomfortable and disconcerting.

Nickel Dime is a good read to discover what happens when these two worlds collide (the author has a PhD and is from a relatively affluent background, taking on menial, minimum wage jobs, typically taken by poor migrant workers).

The narrative is simple and engaging. Critics of the book deemed the author to be too pampered and believe others would have fared better than her if they went through the same experiment.

Overall, it is a good and educational read for all ages to learn more about the world we live in. I would recommend it.

![[Review] Be Our Guest to a Night of Enchantment with Disney’s Beauty and the Beast in Singapore This December [Review] Be Our Guest to a Night of Enchantment with Disney’s Beauty and the Beast in Singapore This December - Alvinology](https://media.alvinology.com/uploads/2025/12/Screenshot-2025-12-14-195843-110x110.png)

![[Review] Tim Ho Wan’s Limited Edition East-Meets-West Menu Brings Festive Flavours to Dim Sum [Review] Tim Ho Wan’s Limited Edition East-Meets-West Menu Brings Festive Flavours to Dim Sum - Alvinology](https://media.alvinology.com/uploads/2025/12/6194907278834600928-110x110.jpg)

![[Book Review] Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America by Barbara Ehrenreich [Book Review] Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America by Barbara Ehrenreich - Alvinology](https://alvinology.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/9604926871_fb8192bab9_o.jpg)