There was a hush when we entered the room.

Despite the shafts of sunlight shining in through the windows, it felt gloomy.

Or perhaps it was my imagination, as I had read about all the horrors that took place here in the late 1970s.

But signs of those tumultuous times still exist today, from the barb wires to the crude wooden and concrete cells to the rusting bed frames with shackles at each end.

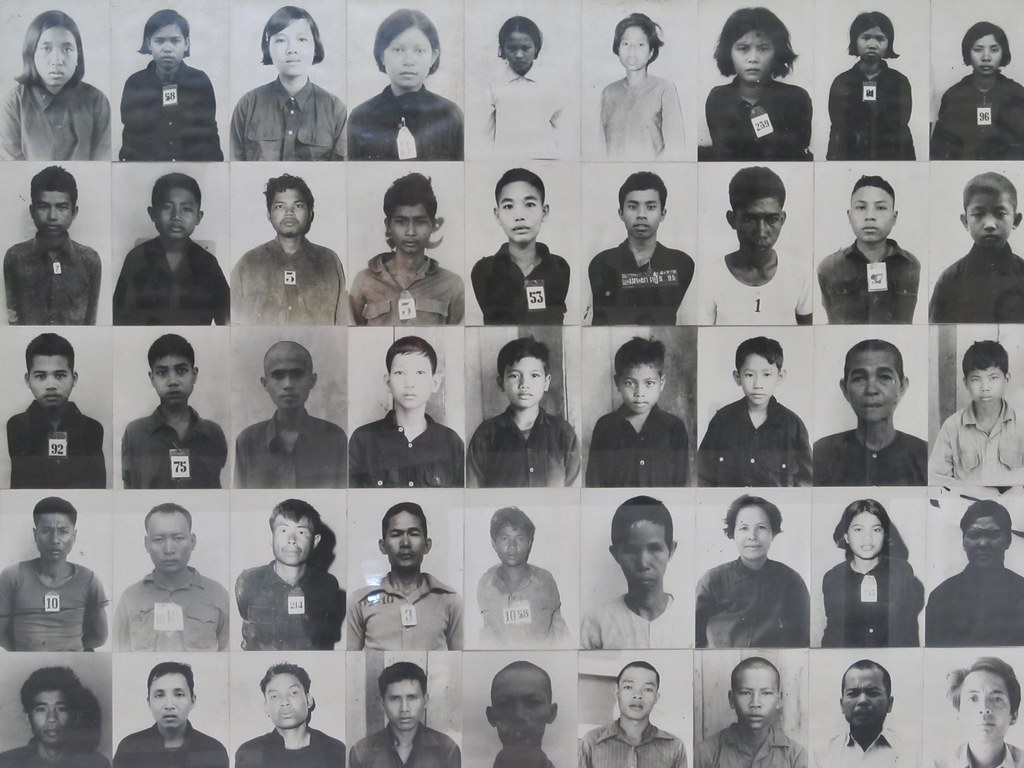

Welcome to S-21, a former high school in Phnom Penh which was used as a notorious prison by the murderous Khmer Rouge regime.

Back in the 70s, S-21 was one of at least 150 execution centres in Cambodia.

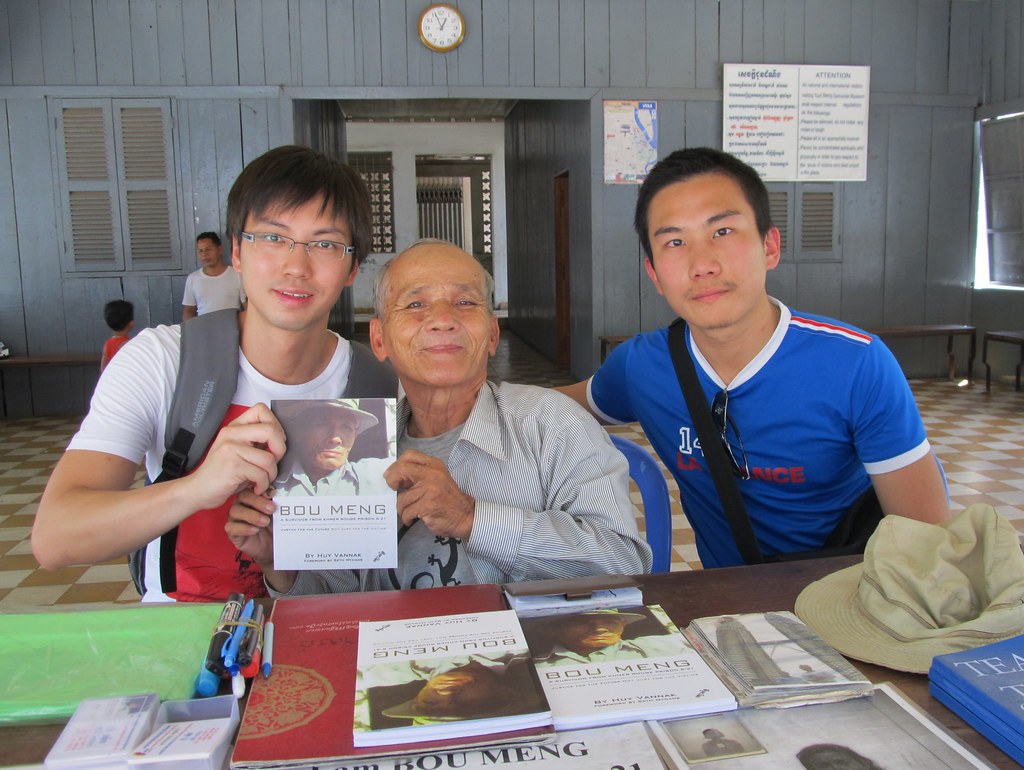

And of the estimated 17,00 people imprisoned there, only 12 people were known to have survived.

Today, it is known as the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, and it’s one of the ‘attractions’ for visitors to the Cambodian capital.

Such a phenomenon involving travel to sites historically associated with death and tragedy is known as dark tourism.

And it’s apparently a rising trend.

In 2012, for instance, 1.43 million people visited Auschwitz, a record figure for the UNESCO Heritage Site.

And visits by foreign tourists to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum hit a record high of 200,086 in 2013

So why do some travellers like to walk on the dark side?

For some, like me, nothing beats seeing it with your own eyes.

I mean, it’s certainly different from reading about it in a book or watching it on television.

Somehow, it feels less detached and more personal.

Like S-21, for instance, when I read about the cramped prison cells, I know how cramped those cells were.

I also saw their view of a world beyond the barbed wires to which they had no hope of returning.

But of course, dark tourism has its fair share of detractors who say it’s exploitative.

They argue that no one should be gaining from others’ suffering.

And I can see where they’re coming from, what with the souvenir shops selling trinkets and other tourist memorabilia at some of these sites.

But I also think that keeping and maintaining such sites help to keep the memory of what happened in these places alive.

It also teaches us the horrors that men can heap on other men, in the name of religion, race or ideology.

For instance, nothing brings home the horrors of war better than a stroll through Sarajevo’s neighbourhoods where former parks now hold rows upon rows of grave stones.

For those too young to remember, in the early 1990s, Sarajevo was where the longest siege of a capital city in modern history took place.

Over three-and-a-half years of war, more than 12,000 people were killed and 50,000 wounded.

And though we’re fast approaching the 20th anniversary of the end of the war, signs of the siege still remain in Sarajevo and across the rest of Bosnia & Herzegovina which was also besieged by warfare.

In the town of Mostar, for instance, the parts of the old town near the river have been lovingly restored.

But wander just ten to fifteen minutes away from the river on either side, and the reminders of the war come into sight.

Besides the buildings pockmarked with bullet holes, there were also gravestones in former parks, just like in the capital city, Sarajevo.

As I walked back to the rebuilt Mostar Bridge, which was destroyed in the war, I noticed a small plaque by the side of a building.

It read, “Don’t Forget”.

And perhaps that just about sums up how I feel about sites associated with dark tourism – that we should never forget the atrocities that mankind is capable of.

So what about you?

Do you prefer holidays to only happy, shiny places?

Or would you seek out sites that highlight the worst of the human race?