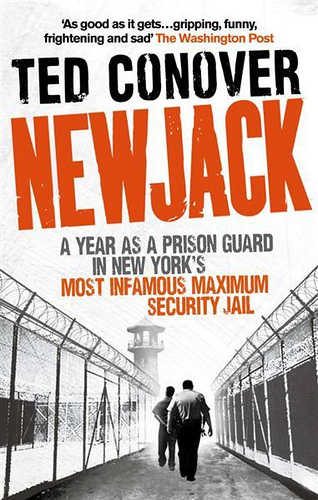

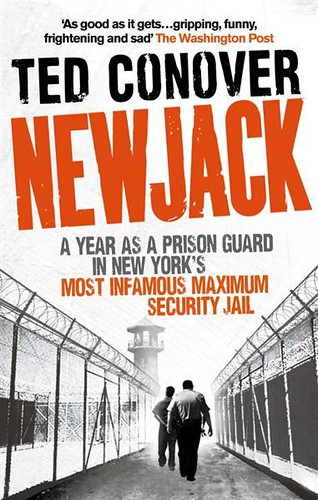

Ted Conover is an American author and journalist, best known for his participatory investigations; riding the rails with tramps, traveling with Mexican undocumented workers, and of course, working at Sing Sing prison which the book, Newjack is based on.

Denied access to report on Sing Sing, New York’s maximum security jail, Conover went undercover, spending a year as a rookie office, or “newjack”.

The book is a winner of the National Book Critics Award for Non-Fiction and a Pulitzer Prize Finalist.

Enter the grimy, mundane and underrated lives of prison guards who risk potential assaults from high risk inmates on a daily basis. Conover documented his stint as a prison guard, right from the point when he sat for his entrance examination, went through boot camp to his posting at Sing Sing.

Reading much of the book reminds me of the crap experience I had going through BMT and my posting to Tuas Naval Base as a regimental police during my two and a half years serving NS (National Service or National Slavery depending on how you see it).

Of course, what Conover went through was much more intense as he had to come into daily contacts with murderers and other convicts of the worst kinds while I had just to deal with stiffening, forced regimentation. Nonetheless, that crappy feeling of serving an inescapable life-sentence of mundane existence prevails in both instances.

I won’t say I did not learn anything from my NS experience, much like Conover won’t deny that Sing Sing did enrich his worldview. However, if given a choice to do it again or extend my service for a few more years, no thanks.

Substitute the term “newjack” with “xin jiao (new bird in Hokkien)” and most Singaporean males will understand all the pain and humiliation being branded a newjack encompasses.

A prison system, similar to a military system thrives on a strict hierarchical pecking order to function. The old prison guards and long serving inmates systematically exploit and bullies the newjacks in Sing Sing, feeding off their inexperience; the “lao jiao (old bird in Hokkien)” and the regulars systematically expolit and bullies the xin jiao in the Singapore army for the same reason.

As Conover recounts his experience of how a particularly sadistic veteran prison guard routinely picks on newjacks, chiding and shaming them at every excuse, I am reminded of a few particularly detestable lao jiao back when I was a xin jiao in Tuas Naval Base.

I still remember the names of these dickheads, but I won’t name them in full so as not to stoop to their level of low. Their surnames are Ong, Wong and Han. The first made me board a seaboat with combat boots simply because he was too lazy to go down to the sea centre himself. I could have drowned and died if I fell into the water on hindsight. The latter two enjoy ordering newbies to clean up after their meals; fold blankets for them; among other insulting tasks that rendered them handicaps in my view. If the three of you are reading this, shame on you. I always regretted not telling them these in their faces before they ORD-ed. They were shiny examples of what I vowed not to become when I became a lao jiao myself (and I didn’t).

Of course, amidst the grim and bitterness, there are always the good people. Conover recounts his odd camaraderie formed with a few inmates and the kindness extended by some of the fellow guards. These were what kept him going in an otherwise thankless job. Same for me in NS. The good guys balance the bad eggs.

Due to many of the parallels between working as a prison guard in America and serving as a forced conscript in the Singapore army, I believe Newjack will be an enjoyable read for most Singaporean males. I did.

![[Review] Fireplace by Bedrock Launches Unlimited Wood Fired Brunch with Festive Treats at One Holland Village [Review] Fireplace by Bedrock Launches Unlimited Wood Fired Brunch with Festive Treats at One Holland Village - Alvinology](https://media.alvinology.com/uploads/2025/12/firestar-by-bedrock-brunch-grilled-25-110x110.jpg)